Light and wellness: A circadian approach to lighting design

At Arup, we’re working to sort out the human and technical complexities behind the quite-natural idea of circadian lighting, determining best practice through extensive research and more than a little self-experimentation.

Global and Americas Lighting Design Leader

Brian Stacy

Principal

Putting human-centric thinking and approaches at the heart of design is a key first principle — the benefits have been tested and proved. Our role as designers is to create environments that are comfortable, engaging, and responsive to occupant needs.

We’re constantly learning more about how our conceptual hierarchy, material selection, internal programming, and where and how we build impacts occupant well-being. So how do we, as lighting designers, consistently up the ante in creating environments that aren’t just functional, but beautiful and socially useful?

By letting our physiological systems lead the way. Starting more than a decade ago, our lighting design team immersed ourselves in the latest groundbreaking research on circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are driven by internal biological clocks that operate on a 24-hour, day/night schedule meant to optimize our physiology.

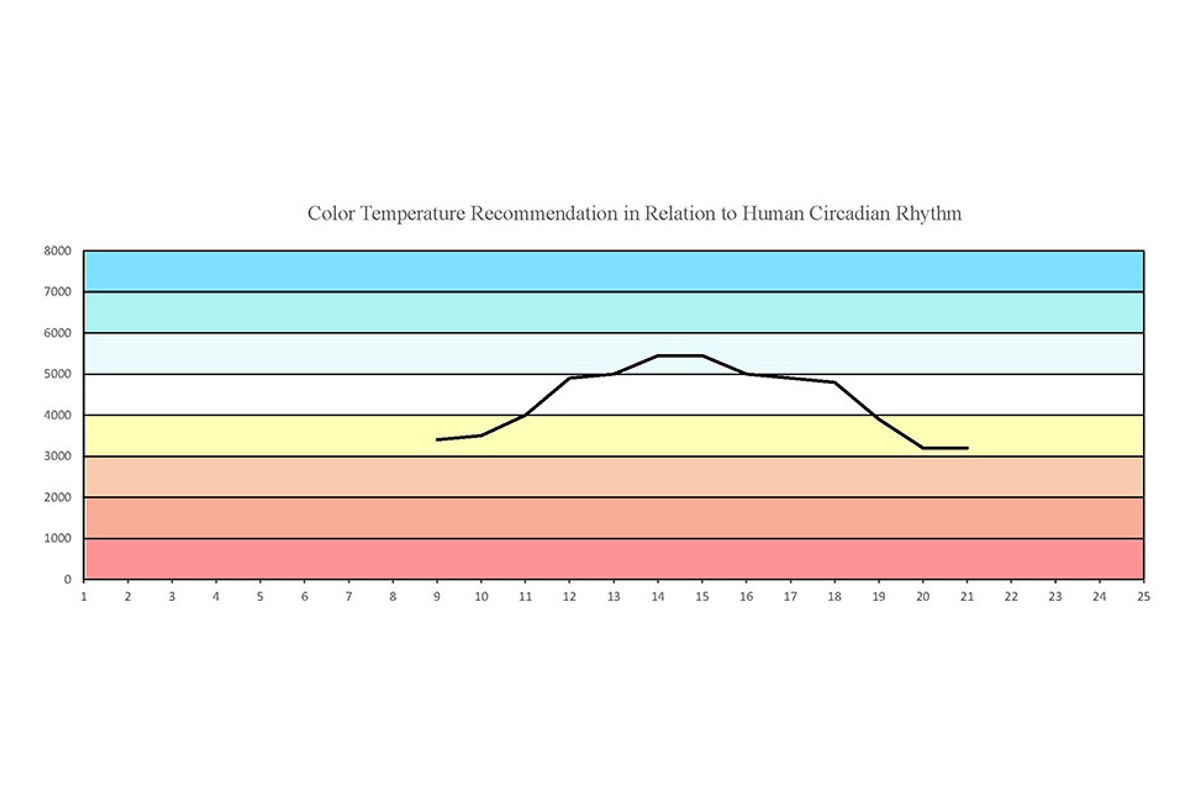

The intent of circadian lighting design is to work in harmony with our internal clocks by providing ample access to daylight or, when daylight is unavailable, modulating the intensity, spectrum, and color of electric light in symbiosis with the natural lighting cycle. This harmony should amplify occupant comfort and productivity and create a healthier visual environment and experience. It is important to note that the wavelengths that impact our biological rhythm can be modified without shifting the visual appearance of the light color. We believe there is also a psychological benefit, even on a subconscious level, to shifting the color temperature because it reinforces a connection to the outdoors.

Sounds easy enough, right? In reality, circadian lighting design is more of a lengthy experiment than an authoritative design standard. In fact, there’s no universally agreed upon guidance — yet. At Arup, we’re working to sort out the human and technical complexities behind this quite-natural idea, determining best practice through extensive research and more than a little self-experimentation.

Research in action

The basics of circadian lighting research started in the ’60s and ’70s around seasonal affective disorder. In the ’90s, our Research and Development team (the forbears of Foresight, Research and Innovation) put together our first research project focused on how seasonal affective disorder impacts office workers.

Over the last five years, we’ve had several internal research projects where staff delve into the leading papers in scientific journals about the effect of lighting on the circadian system. This work created a knowledge base of the demonstrable positive effects circadian lighting can have on office workers, healthcare workers — particularly shift workers — and even hospital patients.

Toby Lewis, a fellow Arup lighting designer from our San Francisco office, noted recently in an interview that the move toward circadian lighting could be seen as experimentation on human health with possible negative side-effects, before those effects are fully understood. She made the point that society has been experimenting with electric lighting sources in our built environment for decades and decades without even thinking about the physiological and biological impacts. Now that the industry is starting to understand the physiological effects, Toby was rightly saying that shifting color temperature in indoor lighting systems to more closely match what’s happening outdoors is a reasonable next step in the electric lighting experiment that likely offers more positive health outcomes. She notes that it’s important to acknowledge that we as lighting designers are not physicians, and cautions end users against introducing high amounts of blue wave lengths after dark.

One of the first projects where we could put our research intro practice was the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Diego, California. Implementing a circadian lighting system in the hospital was a natural way to enhance the patient recovery process and create a healthier work environment for staff — all while supplying Kaiser with regular data they can utilize for future design decisions.

In speaking with my colleague Jake Wayne from our Boston office, he posed the argument that because of the experimental nature of these systems, flexibility is vital. A key point Jake made was that as research continues, and we learn more about actual biological responses, our clients should have the ability to change their programming to update or modify how it is used. I couldn’t agree more.

It’s no secret that better sleep leads to faster healing but getting a decent night’s sleep in a hospital isn’t easy. We designed an all-LED room lighting system that delivers “cooler” (rich in blue wavelengths) light during the day to promote wakefulness and transitions to “warmer” low-intensity light in the early mornings and evenings for rest and recovery. The lighting effectively reinforces healthy circadian rhythms, which in turn supports smoother recovery time.

More than a little self-experimentation

Circadian lighting systems aren’t something we’re just recommending to clients. Our most ambitious experiments are done on our own turf. Starting with large-scale renovation projects in our San Francisco, Boston, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Toronto offices, circadian lighting design is Arup’s new normal.

Traditional office lighting design typically has one color temperature tuned to the horizontal work surface, whereas in our Boston office we're thinking about the quantity of light that actually reaches the eye as well as the color profile of that light. A circadian lighting system requires a spectrum of color temperature and intensity that follows a specific light curve, adapting the quality of light based on the time of day, as well as the local conditions. Thus, the curve we have in Boston is going to be a little bit different than the curve we use in Los Angeles.

Research is still evolving on how to tune circadian systems based on their actual latitudes and available daylight over the course of the day and year. Our body clocks’ cycles adjust to the fluctuations of light from sunrise to sunset, including the changing length of the day throughout the year, as well as to other factors like cloud cover. This stems from the fact that different types of light affect the suppression of melatonin, which regulates our instinct to sleep. This is one area where there’s more exciting research to be done.

The variable-color-temperature lighting and ambient light quality throughout the offices far exceeds what industry standards like WELL qualify as circadian lighting. Even though we achieved WELL Gold certification for the Boston office, our designers always try to go beyond checking a box. We use our home projects to test the limits of lighting design and improve the advice we can offer on our next project. And, of course, we’re working toward a healthier and more comfortable place to work.

Circadian lighting moves into the mainstream

For a very long time, there's been a separation between daylight and electric lighting, and Arup has been at the forefront of work to integrate the two. Now we’re seeing an uptick in the rest of the industry.

Circadian lighting, while still evolving, is no longer just a dream. Lately we’ve seen requests from major commercial clients asking for large-scale, human-centered lighting systems in their new facilities. On the other end of the spectrum are consumer products featuring tunable white-lighting technology via an app on your smartphone.

The future of interior and exterior lighting design certainly lies in this balance of quality daylight and electric light working together to support our human circadian adaptation. And the logical extension of this is that lighting design will eventually start to drive building shape and aperture. And it may happen sooner than you’d think. The healthiest, most comfortable, and most productive spaces will be those designed from the inside out.

Get in touch with our team

Insights

Explore more design insights

Bringing nature inside: how CapitaLand uses biophilic design to cool buildings and boost wellbeing

The sustainable route to improving road safety

How can multi-trade integrated mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MiMEP) design enhance construction?

Did COP28 create a buildings breakthrough?