Global economic interdependencies: the key to achieving emission reductions?

In the first of our Transitioning to a Net Zero World series, this we explore the challenge of recognising and addressing global interdependencies in well-known proposals to mitigate climate change.

Ritu Garg

Associate

Last updated: September 2023

When it comes to climate action, we tend to focus on what is needed in terms of solutions, actions, visions, plans.

Why is it that despite our knowledge and an increasing focus on practical ideas to address climate change, we continue to struggle to rein in greenhouse gas emissions and, collectively, we have failed to achieve the substantive reductions urgently required? Are we targeting the true barriers to a net zero transition?

As part of a multi-year study led by Arup University's Foresight faculty, we highlight three fundamental challenges, that we argue continue to act as systemic barriers to a successful, at-scale global transition to net zero.

This article explores the challenge of recognising and addressing global interdependencies in well-known proposals to mitigate climate change.

A global back-and-forth

Climate targets and regulations are defined nationally, while production and consumption take place globally. Big businesses routinely announce targets to reduce their emissions but outsource emissions-intensive processes further down their supply chains. At the same time, governments understandably struggle to prioritise climate action in the face of day-to-day pressures and maintaining socio-political stability.

Action to address the climate crisis must recognise and grapple with the global nature of trade, industry, production and consumption. A large proportion of emissions are driven by decisions that link to global supply chains. Regulations and financial incentives that aim to reduce emissions without acknowledging these global interdependencies, merely shift impact and carbon intensive activities to more vulnerable, less developed countries. They don’t drive real change.

The food we eat, the things we make

Two central sectors of the global economy are instructive on this issue. Agriculture and industry are the most globally interdependent sectors and combined make up nearly half of global greenhouse gas emissions. International trade and supply chains in these sectors drive markets, scale of activity, and operations.

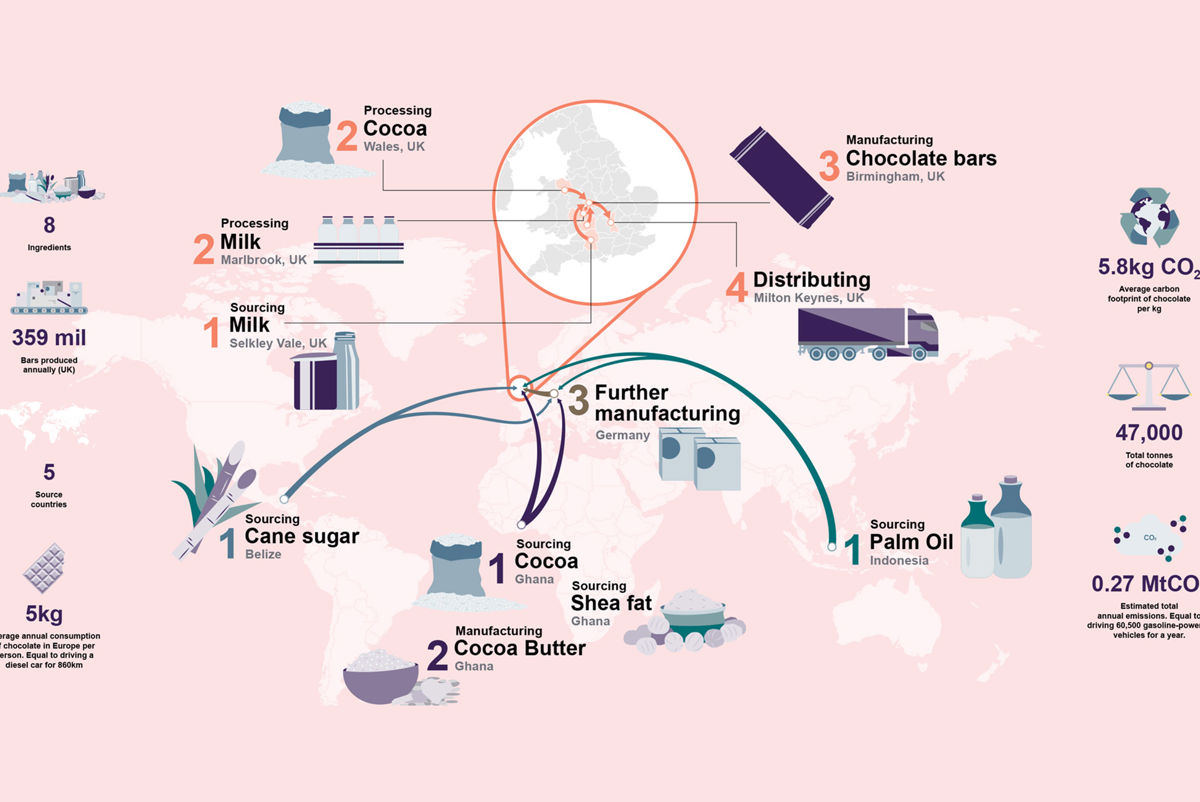

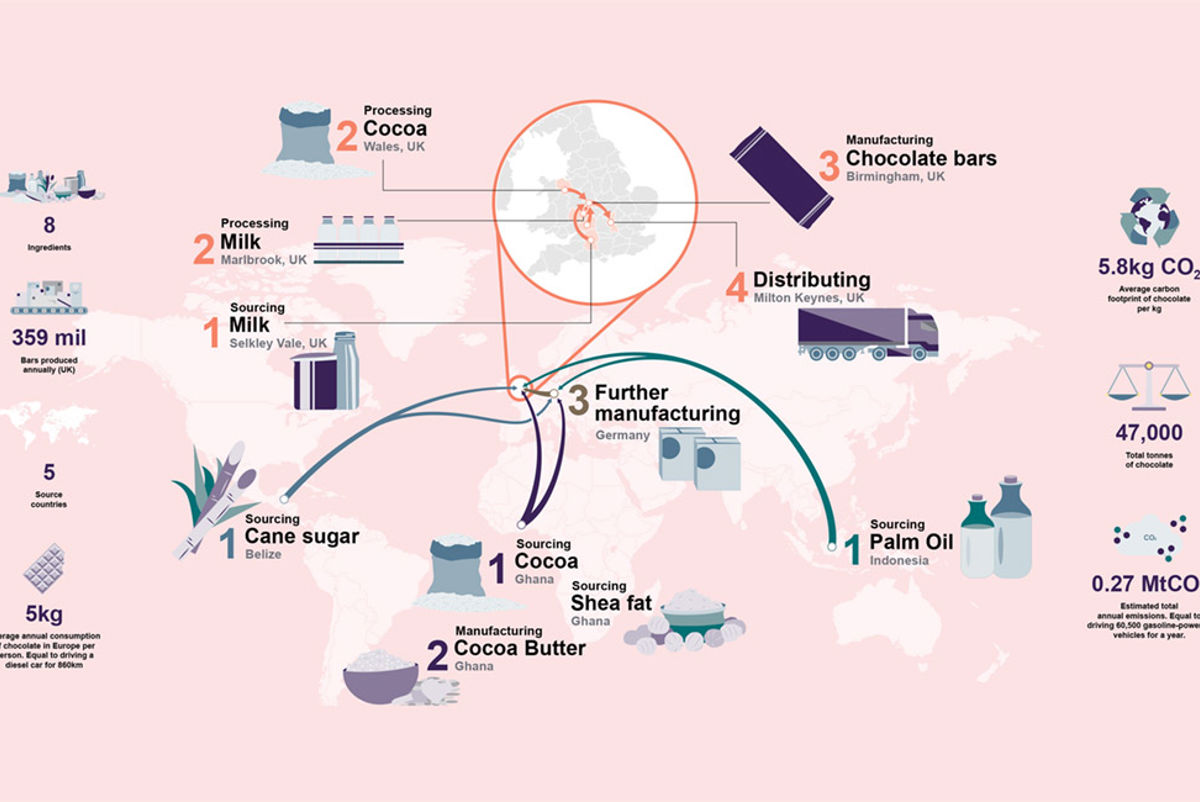

Take a single, familiar product to shoppers worldwide: a simple chocolate bar. One UK brand produces a bar with only eight ingredients, yet the underlying supply and production chain involves materials and manufacturing in at least four different countries:

Supply chain complexity increases immensely for more sophisticated products that rely on distinct materials, skills and knowledge, and processes across different nations. We know it is common for the design, ownership, and demand for a product to sit in an entirely different part of the world from where the product is produced (and where associated emissions-intensive activities required to create the product occur). The role and responsibility of different nations, therefore, in reducing agricultural and industrial emissions is not as simple as tracking and measuring their domestic activities.

Climate, geography, politics and access to natural resources have shaped the role individual countries play in the global agriculture and industry markets. In addition, varying levels of governance and regulation make some regions more susceptible to environmental and/or social exploitation. This implies that the value to the local economy and cost of producing the same product – as well as the social and legislative pressure for mitigation of impact – can vary greatly by region.

As an example, the food and agricultural sector in Brazil – the world’s largest net exporter of agricultural goods – accounted for nearly 30% of its GDP in 2021 (US government figures). Despite global and domestic pressure to preserve and better manage its vast forest land, the economic significance of agriculture in Brazil has tended to weaken government-led action to protect its internationally prized forests. Simultaneously, Brazil supplies agricultural and food products to 222 countries. The rest of the world is reliant on its food production and is the true source of growing demand for arable land in Brazil. About 40% of the country’s second largest biome, the Cerrados Forest, has been cleared for crops and pastureland.

Without a more sophisticated understanding of the roles played by different actors (and regions across key supply chains and of the critical drivers for emissions-intensive activities), our efforts to decarbonise lead to little change, or even stimulate perverse and unintended consequences that undo any gains.

Tools for the job

We need a globally consistent, border-agnostic mechanism for tracking and managing consumption and production in both agriculture and industry if we are to reduce emissions effectively.

A robust and comprehensive global carbon tax scheme is one option. Another solution could be a single mandatory framework for all major corporations with enforceable consequences overseen by an entity with legal power and with a system for monitoring, reporting, and reducing emissions across nations. Attempts to introduce such solutions have taken place and are continually under debate, but until they are implemented effectively, we will continue to neglect the reality of global interdependencies and greatly limit the effectiveness of our proposals to achieve net zero emissions.

Net zero: long-term ambition vs near-term priorities

Global interdependencies are also shaped directly by the conditions internal to nations. Many nations resistant to climate action face distinct, near-term social and economic challenges that hinder their ability to act on climate change. Many countries are still struggling to alleviate poverty, achieve political stability, meet their populations’ need for reliable power, or manage existing national debts. Indonesia, as one example, is the largest coal exporter worldwide and the world’s largest producer of palm oil, which accounts for one third of recent deforestation. With ten percent of Indonesia’s population living below the poverty line, navigating real climate action and transitioning away from coal is inextricably linked with Indonesia's current economy and the need to envisage its future through the lens of a global green economy.

By studying different national contexts, we know there are significant and specific challenges that each nation must navigate. Our research also makes clear that some of the core barriers are common amongst many countries attempting to address climate change.

Misalignment between actions taken for economic advancement and those needed to tackle climate change, frequent changes in governments and a resulting fluctuation in the strength of commitment to climate action, and lack of immediate and serious legal consequences for missing climate targets are some of the common challenges that nations face.

Ritu Garg

Associate, Arup

Immediate political pressures will always be present, making it essential for political leaders to acknowledge that nations cannot succeed in taking action on climate change if they treat climate change policy as an isolated agenda item, separate from other national priorities. To truly enable a long-term commitment towards tackling climate change, nations must fix constraints on emissions within every national strategy and agenda, whether it relates to social or economic issues, or ambitions and investment for technology and innovation.

Coordinate to cut emissions

Stronger and more effective international coordination to tackle climate change and the challenge of ‘global interdependencies’ is ultimately what is needed. The United Nation’s annual climate summits – the conference of parties, COPs – currently provide the best barometer of global commitment and coordination. While these have seen some political progress, they have been insufficient in achieving real and lasting emissions reductions.

The latest UN assessment concluded that the commitments made by nations (these are called nationally determined contributions, NDCs, and they set out each nation’s proposed goals and actions for reducing emissions) in 2022 would actually allow an increase in global emissions by 10.6% by 2030, if fully implemented. Yet the whole point of NDCs is to identify actions to drive a 45% reduction in emissions and to limit global increase in the Earth’s surface temperature to 1.5°C. We are off track, to say the least.

Download

Our Foresight team’s report, Transitioning to a Net Zero World, explores some of the key areas of tension and complexities in tackling the global interdependencies that shape the climate change problem. In our research:

- We raise questions highlighting specific challenges and perspectives that must be addressed in the agriculture and industry sectors to transition to a net zero world.

- We consider context-specific challenges and opportunities for individual nations to explore how solutions, roles, and areas of focus must vary by region.

Read more articles in this series

Get in touch with our team

Insights

Explore more decarbonisation insights

Why ports have a future as green energy hubs

Timber buildings are gaining appeal – but what are the whole life carbon savings?

Sustainable Forces Special Episode Momentus 2025: How can Asia Pacific lead the net zero transition?

How can we cost-effectively convert hospitals to a clean energy future?