A new understanding of the green economy

The importance of decarbonisation has been recognised for decades, and much progress has been made. But the green economy is about far more than that.

Australasia Strategy and Insights Leader

Brice Richard

Associate Principle

Last updated: November 2022

In response to the growing climate crisis, a wave of green technologies, expertise and energy sources have emerged. As a result, we can now discern the emergence of a green economy, one that harnesses human invention to tackle existential issues for the planet, and provide the engine for the economic growth and job creation of tomorrow. But what exactly is the green economy? How big is it and what is its potential? And can it produce an inclusive prosperity alongside the environmental sustainability we urgently need?

These are the questions that a team of climate specialists, economists and sectoral experts from Arup and Oxford Economics have spent the last 12 months addressing. Our work has led to a strategic framework to help governments, businesses, investors and communities understand, size and even more importantly capture the green economy opportunity.

The importance of decarbonisation has been recognised for decades, and much progress has been made. But the green economy is about far more than that. Our definition encompasses all the primary and secondary effects of the global commitments made at COP21 and followed up at COP26 in 2021 to create a much broader and deeper understanding of the Green Economy opportunity.

Defining the green economy

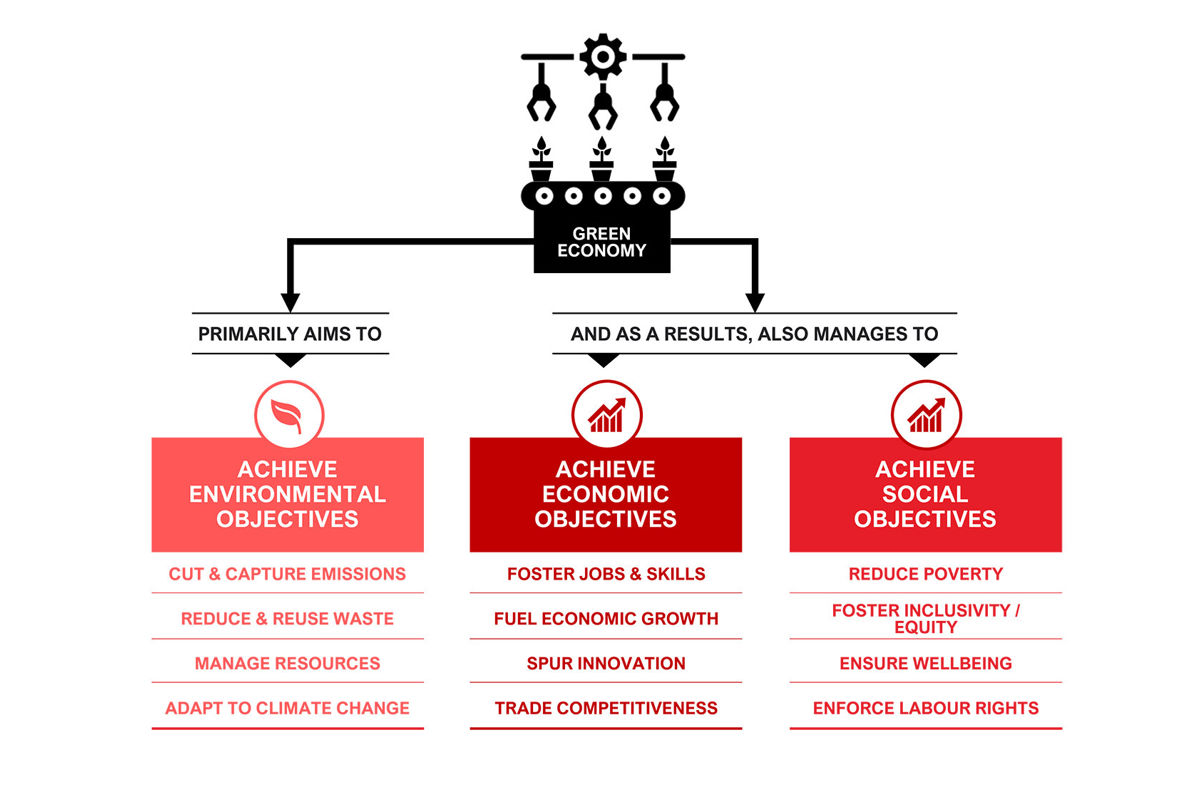

The green economy is an economic model which not only reduces the impact of production and consumption on the environment, but creates a virtuous relationship between economic growth and environmental wellbeing. It’s an economy, long anticipated, that meets specific environmental objectives (primary objective), and in the process creates additional prosperity and social benefits (secondary objective).

A green economy is indeed about far more than emission reduction. It also builds our capacity to adapt to climate change, develop circular systems and reduce waste and material consumption. It leads to greater reuse of materials and not just protection but promotion of greater biodiversity.

But the green economy can and should provide economic and social benefits as well. As the graphic above shows, a green economy is also meant to foster greater prosperity, boost local growth and innovation and foster competitiveness, as well as providing a more just and inclusive society.

Beyond compliance

The rise of green finance and post-Covid Green New Deals have led to the development of green taxonomies. Many such green “classifications” are now underway, spearheaded by the EU, China, South Korea and more than 20 other countries. Many green taxonomies, however, are being developed purely from a financial compliance mindset. In doing so, we at Arup believe that they overlook another opportunity: that of a green classification tool to help governments define which strategic green industries to develop, in order to foster green growth and job creation.

We need a green economy definition designed to drive strategic economic policy, rather than only financial compliance. To address this we have developed a truly all-encompassing definition of the green economy for strategic policy making, based on a detailed breakdown of environmental, economic and social outcomes. Atop this is a taxonomy of 500+ green activities that meet these criteria. Building upon existing taxonomies with far greater details, we have built a truly comprehensive vision of what a green economy looks like, and the activities that underpin its development. The final taxonomy is provided in our related report.

The scale of the green economy

The green economy is not a small niche corner of the market, focused on the decarbonisation of polluting industries. It is a vast and expansive ecosystem of activities that permeates all aspects of the economy, and impacts all aspects of the environment.

Our research partners at Oxford Economics have explored the transition to an environmentally sustainable world by 2050, not only in terms of the costs of climate-change mitigation measures, but from the opportunities that greening the global economy might create. They identified three main types of opportunity:

- First, new competitive opportunities that emerge in the process of industry disruption – as certain businesses move quickly to adopt green measures, their operators can benefit from first mover advantages, patenting new discoveries and establishing dominant market positions.

- Second, new green markets will emerge as demand for renewable energies and green technologies create new markets for green goods and services, creating ‘waterfall effects’ throughout the supply chain.

- Third, productivity gains will be made as regions adversely affected by climate change and unsustainable use of natural resources, see those negative effects reversed, leading to a global economy built on a more sustainable footing.

Oxford Economics projected that these new green activities will create an opportunity worth $10.3 trillion to 2050 Global GDP, in 2020 prices, or 5.2% of global GDP that year. The lion’s share of the opportunity is in the manufacturing of electric vehicles and the generation of renewable electricity, plus their vast supply chains.

Drivers of the inevitable

We believe that the environmental discourse has so far been overly dominated by a focus on risk avoidance, compliance, and costs. Yet, little emphasis has been given to the upside of the green action – the value added to the economy, the jobs new green activities create, the power of sustainable action to drive innovation, new expertise, stronger competitiveness. Given the market fearful of investing in stranded assets in the twilight years of the fossil fuel era, we’re seeing greater confidence that the green economy, powered by renewables, will now start to evolve and grow.

Embracing the green economy makes sense for other reasons:

- Global agreements are penalising traditional and dirtier industries: including the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism that aims to stop businesses or countries offshoring their emissions. It is no longer a matter of if, but when investment relocates to greener sectors.

- Increasingly cheaper green technologies and innovation: the cost curves of not only existing renewable energies, but new emerging technologies from carbon capture to integrated water management systems, from hydrogen to smart grid interchanges, are shifting the cost equation of large scale implementation, creating new demand and markets for green products and services.

- Recovery from the energy price shocks of 2022: Consumers and households around the world have been hit hard by the soaring cost of energy and sudden rises in interest rates on borrowing. Economic growth, job creation and overall prosperity will be badly hit in 2023 as a result. Supporting green sectors could provide an important near-term boost to growth.

- Rapidly growing financial innovation: including carbon trading, green finance and sustainable investment mechanisms, are playing a critical role as enablers of the green transformation, backed by investor activism and new green financial products.

Taken together, the direction of travel is clear from any vantage point you adopt.

An economy with purpose

At Arup, we believe that the issues we see today can’t be solved by arbitrarily bolting on a moral vision to raw economic reality. We are more interested in harnessing and shaping the next generation of economic growth to solve longstanding global development issues. It’s usually the poorest and most vulnerable whose livelihoods and homes are first to be affected by physical impact.

Fundamentally the green growth economy must be built on a vision of stability and inclusivity – these are the rational foundations and can be achieved through incentives, regulation and good governance. Environmental action, as my colleagues working on those priorities will tell you, simply have to work for everyone.

So this is our premise: that many of the new green services, technologies and expertise, are already developing rapidly. The green economy is no longer about relying on renewable energy to simply prolong the productive practices of 30 years ago. The green economy is no longer defined by the avoidance of risks and mitigation of threats. It’s about a once in a century opportunity to build a better future for all.

Insights

Discover more about the global green economy opportunity

The Global Green Economy: capturing the opportunity

Capturing the opportunity’ explores how governments, investors and communities can understand the opportunities promised by green economic strategy and take action to build sustainable prosperity.

Identifying the right green economy opportunity

Get in touch with our team